Статьи и публикации

FABERGE AND RUCKERT

Peter Carl Faberge, jeweler to the court of St. Petersburg, was famous both in Russia and in Western Europe in his own day. His main workshops were in St. Petersburg, where he produced many unique objects of fantasy decorated with en plein enameling, jewels, and semi-precious stones. Faberge, however, also sold work in the Old-Russian style. These pieces were made for him not by his St. Petersburg work-masters, but by independent silversmiths working in Moscow. (Although he had a workshop in Moscow as well, no enamel work was done there.) Fedor Ruckert was the workmaster most actively involved in supplying the firm of Faberge with enamels.

Ruckert began his long association with Faberge in 1887, when the latter first opened his Moscow workshop: a beaker presented by Ruckert to Faberge in 1912 bears an inscription commemorating twenty-five years of collaboration (checklist no. 63).10 Although he may have had only forty workmen,u Ruckert's shop was extremely prolific, supplying other large firms and department stores as well as Faberge.

Ruckert was especially well-known for his small enameled paintings, which were used not only on his own works, but which were applied to objects executed by other craftsmen as well. The small box illustrated in figure 9 has a painting after Viktor Vasnetsov's Tsarevich Ivan Riding the Gray Wolf, a scene from the Russian fairy tale, The Firebird. Although marked "Marshak" (a large firm and department store in Kiev), the enamelwork is clearly in Ruckert's style and displays his excellent craftsmanship. A companion box (checklist no. 61) bears Ruckert's mark in addition to the Marshak stamp. Ruckert's enamel-paintings generally have a matte finish, achieved by stoning the surface of the enamel after it had been fired, a technique that only he seems to have mastered. The matte finish lends richness and warmth to the increasingly somber colors favored by Ruckert.

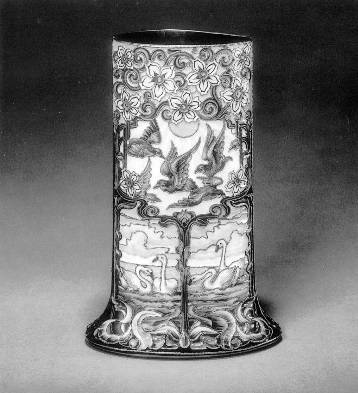

Ruckert's style evolved constantly throughout his career, and these changes are noticeably reflected in his palette. His early works were done in a pastel color scheme. Toward the end of his career, when he made most of his matte enamel-paintings, he used the darker tones of rust, dark blue, brown, and gray. Even when producing objects in a pastel palette similar to that used by contemporary artists working in the Old-Russian style, however, Ruckert moved away from conventional, more naturalistic patterns toward a more stylized design. A striking example exists in his introduction of Art Nouveau motifs in the vase in figure 11. The vine-tree swirling out of the green base seems to take on a life of its own and produces a lyrical effect compared to the more static traditional designs.

Ruckert's later work is easily distinguished not only by its coloring, but also by the metalwork itself. The cloisons in the box shown in figure 9 are used to delineate mushrooms, trees, and birds. Here the wires no longer merely separate the colors; they are used to form designs of their own, and are often coiled into decorative spirals or set in a cross-hatched pattern like railroad tracks. Ruckert was one of the few silversmiths who used granulation, a technique known in Russian metalwork since ancient times. Granulation refers to small pellets of metal, often placed along tendril-like decoration, as in the beaker and plate in figure 10. These objects have scenes painted in grisaille (shades of gray) of well-known Kremlin monuments: the Ivan the Great Bell Tower on the cup, and the Tsar's Cannon and Bell, both the largest ever made, on the plate. The inclusion of such monuments, which were widely used by all the Moscow enamellers, is also evocative of the nationalist spirit of the times.

Ruckert began his long association with Faberge in 1887, when the latter first opened his Moscow workshop: a beaker presented by Ruckert to Faberge in 1912 bears an inscription commemorating twenty-five years of collaboration (checklist no. 63).10 Although he may have had only forty workmen,u Ruckert's shop was extremely prolific, supplying other large firms and department stores as well as Faberge.

Ruckert was especially well-known for his small enameled paintings, which were used not only on his own works, but which were applied to objects executed by other craftsmen as well. The small box illustrated in figure 9 has a painting after Viktor Vasnetsov's Tsarevich Ivan Riding the Gray Wolf, a scene from the Russian fairy tale, The Firebird. Although marked "Marshak" (a large firm and department store in Kiev), the enamelwork is clearly in Ruckert's style and displays his excellent craftsmanship. A companion box (checklist no. 61) bears Ruckert's mark in addition to the Marshak stamp. Ruckert's enamel-paintings generally have a matte finish, achieved by stoning the surface of the enamel after it had been fired, a technique that only he seems to have mastered. The matte finish lends richness and warmth to the increasingly somber colors favored by Ruckert.

Ruckert's style evolved constantly throughout his career, and these changes are noticeably reflected in his palette. His early works were done in a pastel color scheme. Toward the end of his career, when he made most of his matte enamel-paintings, he used the darker tones of rust, dark blue, brown, and gray. Even when producing objects in a pastel palette similar to that used by contemporary artists working in the Old-Russian style, however, Ruckert moved away from conventional, more naturalistic patterns toward a more stylized design. A striking example exists in his introduction of Art Nouveau motifs in the vase in figure 11. The vine-tree swirling out of the green base seems to take on a life of its own and produces a lyrical effect compared to the more static traditional designs.

Ruckert's later work is easily distinguished not only by its coloring, but also by the metalwork itself. The cloisons in the box shown in figure 9 are used to delineate mushrooms, trees, and birds. Here the wires no longer merely separate the colors; they are used to form designs of their own, and are often coiled into decorative spirals or set in a cross-hatched pattern like railroad tracks. Ruckert was one of the few silversmiths who used granulation, a technique known in Russian metalwork since ancient times. Granulation refers to small pellets of metal, often placed along tendril-like decoration, as in the beaker and plate in figure 10. These objects have scenes painted in grisaille (shades of gray) of well-known Kremlin monuments: the Ivan the Great Bell Tower on the cup, and the Tsar's Cannon and Bell, both the largest ever made, on the plate. The inclusion of such monuments, which were widely used by all the Moscow enamellers, is also evocative of the nationalist spirit of the times.

Fig.9

Cigarette Box by the firm of Fedor Ruckert, 1908-17.

(checklist N 60)

(checklist N 60)

Fig. 10

Beaker and Plate by Ruckert, sold by Faberge,

1896-1908

(checklist N 65)

1896-1908

(checklist N 65)

Fig. 11

Flat-Bottomed Vase by the firm of Ruckert,

1896-1908

(checklist N 50)

1896-1908

(checklist N 50)

Fig. 12

Easter Egg by the firm of Ruckert,

1896-1908

(checklist N 47)

1896-1908

(checklist N 47)